It seems that all around us people talk about the government – how it should be structured, who should be in charge of it, whether this or that decision the government made was a good one. Yet rarely do we step back and ask ourselves what criteria we are using when we evaluate these facets of government.

In this article, I propose a shared framework for evaluating governmental structure, makeup, and decision making that is implicit in almost all conversations on the topic. Then, with this framework brought to light, I explore some of the implications for those debates.

The criterion we use to judge a government is quite basic – we simply ask if the government’s existence or actions improves the lives of those it governs. A government whose actions improve the lives of its populace is a legitimate one; one whose actions do not, is not.

This criterion is implicit in all debates about government. When people talk about who should be voted into office, the ultimate basis of their preferences is the improvement they believe those people can bring to the lives of the population. When people discuss the ideal structure of a government (e.g., democracy, aristocracy, tyranny), their goal is to find a structure that best benefits the people involved. Almost no one argues for democracy as a good in itself; they argue for it by claiming that no other form of government allows the population to voice their needs, and thus no other form of government is sufficiently able to address those needs and improve the lives of the population.

For a more concrete example, consider the vaccination debate in the US. While pro-vax parties argued that vaccinations saved lives and reduced harm from illness, anti-vax parties argued that vaccinations were dangerous and untested. Neither of these parties cared in particular about vaccinations in themselves. Instead, they cared whether the government’s decision to promote vaccines would improve the lives of human beings, once again illustrating that it is this criterion that underlies political debate in almost all contexts.

Of course, another key part of the vaccination debate was the question of personal freedom. In other words, how much can the government do to improve our lives, and how much should be left in the hands of individuals to decide for themselves. With the basic criteria of governmental legitimacy in hand, we can return to this conversation and consider it from this new perspective. The question now becomes: how much freedom should the government allow us, in order to best improve our lives?

First, let’s lay out some freedoms that we can all agree should not be permitted under a legitimate government. A government that allows murder or other forms of serious physical violence cannot be legitimate. After all, almost everyone agrees that lives are made worse by death and violence. Thus it follows that a government which prevents these actions is thereby improving the lives of its constituents and, accordingly, is acting legitimately. Other similar basic requirements may be made of a government here, each with differing degrees of general acceptance.

There are other freedoms, however, which are less obviously inviolable. To decide the question for these, it is necessary to think a little more about what we mean when we talk about a government ‘making our lives better.’ After all, what factors make a life a good one, such that facilitating them can make a life better? How we answer this question will decide how we think about almost every contentious feature of government.

Now, naturally, deciding what makes life good is not a simple matter. To see why, note that this isn’t just a matter of what will make people happy. A good life is not necessarily a happy one. No, a good life is a life well lived, a moral life, the life of a good person. So what we’re talking about here is not how a government can make people happy, but how a government can make people into better people, into the best versions of themselves.

In other words, it is nothing less than one’s basic ethical position that is at stake here. This is why discussion of politics is so often considered personal, despite obviously impacting everyone in society. And it’s also why people’s minds are so difficult to change, and why they get so emotional about political matters. Politics is not merely a decision on social organization – it’s a reflection of one’s ethics into the social sphere. Calling my politics bad is, at bottom, calling me a bad person, because my politics is nothing less than my value system, described in terms of social organization instead of individual action.

Still, if we focus on the question of personal freedom, we can outline two major schools of thought. According to the first, a person’s ethics should be their own, and the government should have no part in ethical discourse or in promoting one set of values over another. This is the viewpoint associated with pure Libertarianism, or, in a phrase, the claim that the government is best that governs least. While those who espouse this viewpoint sometimes disavow relativism or skepticism about ethics, it is precisely those metaethical positions that tend to justify this perspective on politics. After all, if ethics is relative to the individual or is otherwise simply unknowable, then mandating it for a whole society cannot be based on any real knowledge of a (on this view non-existent) universal ethical truth, and thus can’t be reasonably be expected to improve their lives. Instead, the government should at most put in place a basic framework of ethics that almost all can agree on (things like don’t kill, don’t torture), and leave the rest up to the individuals to decide. If the government mandated things like vegetarianism or religious decisions or other ethical matters it would be overreaching and making people’s lives worse. Government, according to this perspective, can’t legislate ethics because ethics is a purely personal affair. As a result, the government needs to stay small in order to respect the individual’s ethical decisions.

The second view runs directly counter to this. If we believe there is a single correct ethical system, and that at least the major elements are known to us, then it becomes the government’s task to promote and enforce these ethical standards. After all, by doing so it makes the population more ethical, thus making them better people and improving their lives.

Just to complicate this picture a bit, let’s note that even from this perspective, a lot will depend on what ethical framework we take to be authoritative. If we are utilitarians, for example, improving human lives means filling them with more happiness. Accordingly, we will want a government that maximizes happiness (utility) for the most people. Perhaps personal freedom is still important here, since each individual knows best what makes them happy. But this is no longer freedom to practice your beliefs as you see fit. No, now it’s the freedom to do whatever makes you happy. The government should intervene as little as possible, but not because you have a general right to practice your beliefs. Instead, this preference for non-intervention is based on the idea that people are all unique and the government isn’t super good at making the majority of people happy when it intervenes.

Notice however that if the government took some action that did result in a net increase in human happiness, no matter how paternalistic or overreaching, this action would be authorized under the utilitarian conception of governmental legitimacy. This utilitarian perspective could thus end up being either pro-vax or anti-vax, depending how we weigh the happiness gains from each side, because it does not have any fundamental stake in governmental non-intervention or respect for personal freedoms. With all that said though, utilitarianism has traditionally leaned towards a minimalistic conception of government, usually citing the diversity of human desire as the principal reason (thus the label ‘utilitarian libertarianism’).

Consider now another answer to the question of which is the one correct ethical system. For religious people, their religion represents the one accurate ethical organization of a life. From this perspective, improving human lives means bringing people closer to God. The natural conclusion is thus that a government is best if it brings more people into the one true religion, thereby giving them access to the blessings of God and potentially infinite rewards in heaven. Accordingly, the natural political direction for all religious people is theocracy.

To see this in action, observe that although religious political pundits often seem to advocate for reduced government overreach, in practice this argument is only made when expedient. One can often see these same pundits arguing that government overreach is totally admissible when it favors the values of their religion. For example, they will argue for freedom of religion when it means allowing prayer in schools, but then make religious arguments against abortion and gay marriage. The consistent thread in these otherwise contradictory arguments is the implicit desire for religious theocracy. And they are fully right to desire this – anyone who earnestly believes in infinite rewards awaiting the devout in heaven should be expected to spend every waking moment earning those rewards and convincing others to do the same. Anything less can only be chalked up to lack of faith.

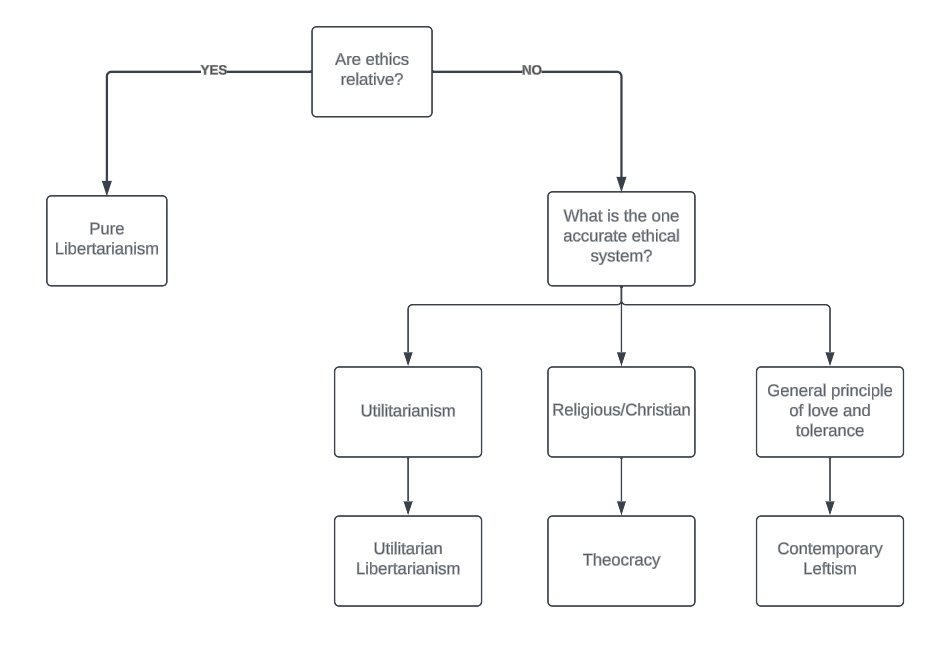

To summarize our discussion thus far, I have made a quick diagram outlining the decision points that underlie these different political perspectives:

This is by no means exhaustive, as there can be any number of ethical systems for which people will advocate, and each of them will have its own attendant political system designed to maximize the goodness of the people who live under that system.

Now let’s bring this all back to the question of personal freedom. It should be clear from what we’ve said so far that a government is authorized to violate our freedoms at any point, provided that those violations improve our lives. Of course, according to several perspectives, most infringements on freedom fail to achieve that goal. But that hardly matters – the bottom line is that on none of these perspectives is there some basic inviolable personal freedom. No, your freedom begins where the government’s ability to improve your life ends.

This has some important consequences. First, free speech and other rights or freedoms, as such, are not of any particular value. Yes, free speech can improve our lives if it helps us understand ethics (pure libertarianism) or helps us be happier (utilitarian libertarianism). But free speech is not something to be valued in itself, and has no place in a theocracy, or really in any ethical system that doesn’t place the locus of ethical correctness in the individual. Indeed, the same could be said of all the various rights enshrined in national constitutions the world over – none of these are of any value except insofar as they improve our lives, and those who claim that they do so improve us are claiming this on the basis of a specific ethical perspective.

Second, all these views advocate that the government can and should promote certain beliefs and ideas to its population. They all agree that there is a right way to see the world, and from this it follows that the lives of a population will be improved if they see the world that way. Accordingly, any given government should promote that perspective. Where these viewpoints disagree is on what that right way to see the world is. Should the government promote ethical relativism, should it promote the valuation of individual happiness over all (utilitarianism), should it promote a religion (theocracy), or should it promote a more nebulous set of values that hasn’t been formally codified into an -ism yet? Regardless of how we answer, the fact remains that the government cannot and should not keep its hands out of our belief systems.

Hopefully seeing things through this lens will help us all be a bit more honest about what we want in political debates, and a bit more introspective about just what exactly our ethical beliefs are. In truth, we all want the government to change society and control people’s behaviors, it’s just a matter of what changes we want to see and what behaviors we want to control. And this perspective should also help make sense of how often the same people who argue for freedom on one issue will argue for intervention on another. Freedom and rights, for most political pundits, are just vague words they can invoke to make their opinion sound good. The truth is that all sides of a political debate want to violate freedoms and control a population. The real question isn’t “should the government control the population?”; instead it’s “what controls will make us better people?”

Leave a comment